Walt Disney may turn in his grave or thaw and drop deader if and when he learns that Bambi, the book he adapted to create the animation classic, was written by a man who is solidly credited as being the anonymous author of a celebrated and notorious work of German erotica.

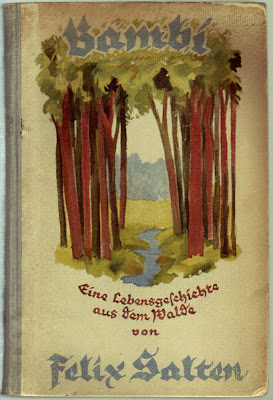

In 1906, an erotic memoir was privately published. Purportedly written by a Viennese prostitute at the end of her life, Josefine Mutzenbacher, oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne, it became a popular success; it is now a very rare book, a first edition copy recently selling for over $6,000. The introduction to the original is signed by “the editor.” The “editor” was, in fact, the anonymous author. That author has been firmly identified as Felix Salten (pseud. of Siegmund Saltzmann), whose claim to fame is as the author of Bambi, Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde, originally published in 1923. The english translation of the story about a male roe deer (yes, Bambi is a boy) was rendered by Whittaker Chambers, the writer and former Communist Party member who gained fame for his testimony against Alger Hiss, and published in 1928 as Bambi, A Life in the Woods.

In 1906, an erotic memoir was privately published. Purportedly written by a Viennese prostitute at the end of her life, Josefine Mutzenbacher, oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne, it became a popular success; it is now a very rare book, a first edition copy recently selling for over $6,000. The introduction to the original is signed by “the editor.” The “editor” was, in fact, the anonymous author. That author has been firmly identified as Felix Salten (pseud. of Siegmund Saltzmann), whose claim to fame is as the author of Bambi, Eine Lebensgeschichte aus dem Walde, originally published in 1923. The english translation of the story about a male roe deer (yes, Bambi is a boy) was rendered by Whittaker Chambers, the writer and former Communist Party member who gained fame for his testimony against Alger Hiss, and published in 1928 as Bambi, A Life in the Woods.

Josefine Mutzenbacher was anonymously and crudely edited and translated into english as Memoirs of Josephine Mutzenbacher, and anonymously published by either the celebrated New York pornographer, Samuel Roth, or Jake Brussel in 1931.

The book in its original German is well-written and, at times poignantly humorous. The vulgarity of the first english edition was rectified by a later, complete translation issued in 1967 by Brandon House Library Editions,  the imprint of respected, Los Angeles-based porn magnate, Milton Luros. The imprint was managed and edited by Brian Kirby, who, because of his fine taste and, significantly, his Luros-owned-but-commanded-by-Kirby imprint of fine, original erotica, Essex House, many consider to be the Maurice Girodias of American erotica. For Brandon House Library Editions Kirby commissioned the greatest program of first (or finest) english translations of erotic literature in the genre’s history.

the imprint of respected, Los Angeles-based porn magnate, Milton Luros. The imprint was managed and edited by Brian Kirby, who, because of his fine taste and, significantly, his Luros-owned-but-commanded-by-Kirby imprint of fine, original erotica, Essex House, many consider to be the Maurice Girodias of American erotica. For Brandon House Library Editions Kirby commissioned the greatest program of first (or finest) english translations of erotic literature in the genre’s history.

“Kirby’s choice of material…was adventurous, and included specially commissioned translations of French and German erotica…the books were often printed on good paper, and the choice of cover art included work by artists such as Rops, Labisse, and Munch” (Kearney, Patrick J. A Catalogue of the Publications of Brandon House Library Editions).

The Brandon House Library Edition, which remains the standard and has been reprinted many times, was translated by Hilary E. Holt, Ph.D. (who provides the edition’s Introduction) under the pseudonym Rudolf Schleifer (he also translated under the pseudonyms Andre Gilbert and Franz Mecklenberg). Holt, a Austrian transplant to the U.S. raised in the last throes of the Austro-Hungary empire and, according to Kirby, a former professor living in a small, dumpy apartment in Hollywood and “a sad old man,” used a copy of the first edition from his personal collection, avoiding later German-Austrian editions which had been “improved” upon. Holt also translated a spurious sequel to Mutzenbacher for Kirby.

In Holt’s Introduction to the Brandon House edition, he relates a conversation he had with Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig in 1930 regarding Salten and this book. According to Holt, Zweig, “the only mortal who worked up enough courage to ask the alleged ghost-writer of the Mutenbacher Memoirs,” told him:

Salten and I were discussing the literary phenomenon of famous authors writing bawdy stories containing four letter words and describing sexual bouts with Rabelaisian frankness. Salten reminded me of the poem Der Herr von Iste by Goethe. I, in turn, mentioned Mark Twain’s bawdy story dealing with the English court of Elizabeth I: 1601.

I thought this a good occasion to question Salten about his alleged authorship of the Mutzenbacher story. He smiled mysteriuosly and sad: ‘If I deny it, youu won’t believe me, and if I admit it, you’ll think I am teasing you. So…’ and he shrugged. To me this was a badly disguised admission. Knowing Salten well, I realized he’d have become very angry at being asked such a question unless he was the author.’

If it comes as a shock to learn that the writer of a classic of children’s literature wrote erotica, you may be further jolted by the fact that other authors of juvenalia wrote erotica, as well. The celebrated children’s book illustrator, Tomi Ungerer, is a prime example His Fornicon. (Rhinoceros Press, 1969, in a limited edition of 500 copies) offers a graphic, surreal, and witty view of wildly imagined sex machines in service to delighted women. Both genres require a particular facility with fantasy.

Meanwhile, Bambi, Disney’s androgynous doe-eyed male roe fawn, is blushing. His creator, Felix Salten, was a faun having fun while writing Josefine Mutzenbacher. Where’s Bambi’s mother when she’s needed most?