As a seasonally appropriate example, think about Valentine’s Day cards. They range from the intricate and flowery to the crude and humorous. They can be costly confections carefully constructed, or cheaply churned-out chaff. They are a microcosm of the evolution of printing and manufacturing, showing the shift from completely handmade items to labor intensive hand-finished factory pieces, to mass produced bulk greeting cards. As the holiday for lovers nears, the University of Oxford‘s Bodleian Library is highlighting its fine collection of Valentine’s Day ephemera with a temporary exhibition. The display reveals the written rituals of courtship in the days before the almost complete impermanence of texting, tweeting, and e-mailing replaced paper tokens of love.

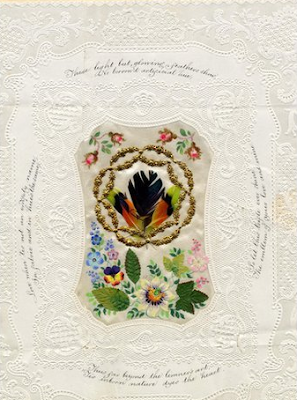

Embossed Lace-paper Valentine With Hand-painted Satin, Scraps, Feathers and Tinselling, Watermarked and Postmarked 1845.

Embossed Lace-paper Valentine With Hand-painted Satin, Scraps, Feathers and Tinselling, Watermarked and Postmarked 1845.

The curators of the university’s rare book library and archive have put together a carefully chosen display of thirty-seven St. Valentine’s Day items from The John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera. The exhibition, entitled The Season For Love, presents an excellent cross-section of nineteenth-century valentines, which illustrate the complex design and manufacturing of love tokens in the Victorian era. The selection ranges from home-made creations fashioned from silk, tinsel, lace, feathers, and artificial flowers, to intricate “dainty wares” that, while manufactured, required hand finishing by several trained artisans, to clumsily colored woodcuts printed on poor-quality pulp paper. Some contain complex puzzles and games, mock maps, and phony bank notes. Others feature ugly caricatures and other images meant to insult rather than inflame the recipient.

Stencil-Colored Woodcut Of An Ugly Spinster c. 1835-40. Verse Reads In Part: “If the devil step’d, old lady, from his regions just below, He couldn’t find a picture like the one before me now.”

Stencil-Colored Woodcut Of An Ugly Spinster c. 1835-40. Verse Reads In Part: “If the devil step’d, old lady, from his regions just below, He couldn’t find a picture like the one before me now.”

The text of the cards is as varied as the imagery, ranging from elaborate verses featuring classical and mythological references, to cheap jokes and crassly insulting humor. The exhibit catalog refers to an article in the London Review of 1865 which lambasted valentine verses both high and low. Lofty language is said to be skillful but utterly predictable, “all ‘thine’ and ‘shine’ and ‘divine’–and of course ‘valentine’–‘bliss’ and ‘kiss’ and ‘beauty’ and ‘duty.'” But the writer’s most scathing words are saved for those who pen the poisonous poetry of the cruelly comic cards: “scandalous productions… wretchedly engraved… an outlet for every kind of spiteful innuendo, for every malicious sneer, for every envious scoff.”

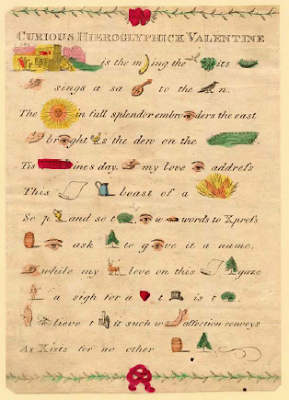

Hand-colored Valentine c. 1840’s. The Pictogram Puzzle Must Be Deciphered To Understand The Expression Of Adoration.

Hand-colored Valentine c. 1840’s. The Pictogram Puzzle Must Be Deciphered To Understand The Expression Of Adoration.The wildly contrasting artistic designs and poetic verses of the cards chosen by the Bodleian Library curators represent a cross-section of Victorian society, from the poshest toffs to the coarsest commoners. These ephemeral items reflect the lovers of their time with an immediacy that conventional written volumes could never hope to achieve. Will the impermanence of our online communication prevent us from leaving a legacy of contemporary courtship equal to the valentines of the Victorians? If so, the history of our time will prove the poorer for having turned the transitory into the transparent.