“Lucius Beebe, who was larger than life, is dead. The famous author suffered a heart attack shortly after his ritual morning Turkish bath in his Hillsborough winter home yesterday” (obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, Feb. 4, 1966).

“If anything is worth doing it is worth doing in style, and on your own terms, and nobody’s Goddamned else’s!” – Lucius Beebe.

“I admire most of all The Renaissance Man, and if it can be said without pretentiousness, I like to think of myself as one, at least in some small measure. Not a Michelangelo, mark you, but perhaps a poor man’s Cellini or a road company Cosimo de’ Medici … the Renaissance Man did a number of things, many of them well, a few beautifully. He was no damned specialist.” – Lucius Beebe, as quoted by Herb Caen.

Yet Lucius Morris Beebe (1902 – 1966) was a specialist. His specialty was life.

He also specialized in a particular subject area that has many avid book collectors. He was a gentleman-scholar, a prolific writer of books that remain key references in thier field, and some that have become highly collectible, particularly those published by the legendary San Francisco bookman and giant in the antiquarian book trade, Warren R, Howell, of Howells Books, in beautifully designed limited editions with fine production values issued by Howell-North Press.

Lucius Beebe was born into the opulence and splendor of The Gilded Age by an extremely wealthy Boston mercantile and banking family. As an undergraduate at both Harvard and Yale, he was an outstanding student – and troublemaker of prodigious talent and dash. He had a roulette wheel and fully equipped bar in his dorm room. It was his custom, classmates recalled, to appear for class on Monday mornings in full evening dress, wearing a monocle and carrying a gold-headed cane.

He once attempted to t.p. J.P. Morgan’s yacht from above, bombing it with rolls of toilet paper from an airplane he’d chartered just for the occasion.

In recognition and celebration of Beebe’s many accomplishments, Harvard and Yale invited him to be expelled, an invitation beyond his control to decline.

When not pursuing hedonism with a vengeance, he earned distinction as an undergraduate poet and won his Master’s degree (finally) with a thesis on the poetry of Edwin Arlington Robinson, published in 1928 in an edition of twenty-five copies. In 1931, he wrote a biography of the poet.

He joined the staff of the New York Herald-Tribune in 1929, and soon snapped Manhattan to full attention with his presence. Journalist Walter Gibbs noted the “outrageous majesty of his appearance,” and recalled witnessing the startling disjunction of the budding journalist covering a “negligible fire in a morning coat, and a tedious dinner of the New York Landscape Gardening society in top hat and tails.”

In 1934 he began a daily newspaper column that ran for ten years. This New York quickly became must-reading, avidly read by 1.5 million New Yorkers of all classes, who marveled at Beebe’s inordinate charm and dry wit (he once wrote, “Mrs. Graham Fair Vanderbilt’s butler is reported to have been dismissed for saying, ‘O.K., Madam …'”), qualities that greatly mitigated his monumental snobbishness. He chronicled “cafe society,” a term he coined to describe the mere 500 people in the world who, by his standards, qualified. To be a member of Beebe’s cafe society you had to be rich and/or famous but far more to the point, you had to live an interesting, adventurous life with élan and panache.

A typical evening for Beebe would begin at the opera, followed by expeditions to and through El Morocco, “21”, the Colony, and the Stork Club. Afterward, he’d often stop into a Broadway coffee shop with friends – Noel Coward, for instance – for a bowl of chili. Only afterward would he write his column. He was, despite his decadent habits, a disciplined writer and work horse.

His satorial splendor was legendary. He routinely sported custom-made suits from Savile Row, thick gold watch chains, and derby hats. He endured five kidney-stone operations – the result of his love of fine food, cigars, and distilled spirits – but was cavalier about them; they were simply a small price to pay for living the good life.

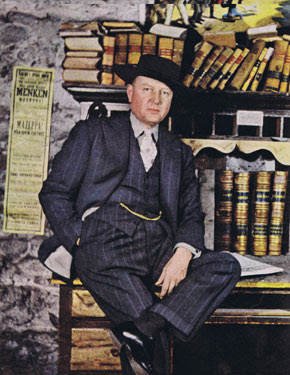

This photograph originally appeared in Holiday, the travel

magazine for the social set that Beebe regularly contributed to.

It should come as no surprise that Lucius Beebe wrote The Stork Club Bar Book (1946), a highly desirable (unsigned, fine copies in like dust jackets are currently fetching up to $450), essential volume for those besotted by rare cocktail recipe books, a spirited area of book collection; its price is the proof.

Famed columnist and radio broadcaster, Walter Winchell, called him “Luscious Lucius,” which may have been a veiled allusion to Beebe’s homosexuality as much as a commentary on his style. Beebe didn’t much care what anyone thought about it; he was one of the first gay men to be open about his relationships. He would respond to whispers with a sharp “go to hell.”

Given all of the above, his area of scholarship and literary legacy seem most unlikely. It may come as a shock to learn that “Luscious Lucius” Beebe was, and remains, the greatest writer on railroading that America has ever produced, his books fundamental to any serious collection on the subject.

Beebe, dressed down (but not out) taking photographs of trains.

Beebe, dressed down (but not out) taking photographs of trains.He was America’s premier historian, scholar and photographer

of America’s passenger trains.

In 1940, Beebe visited Virginia City, Nevada, and fell in love with the historic mining town, often returning to visit. Two years earlier, he began his love affair with trains and railroads and published his first book on the subject. In 1949, tired of the social scene he created, he moved there and bought a newspaper, The Territorial Enterprise, to which Mark Twain had contributed, 1862-1868; the stories in Roughing It! first appeared in its pages.

Beebe moved into the town’s oldest, largest home, the opulent Piper mansion. He had two personal railroad cars, The Gold Coast and Virginia City, custom-made for himself and his personal and professional partner, Charles Clegg. They were the most lavish and expensively outfitted private railway cars in the United States, the period equivalent of today’s private jet. They were decorated in an over the top Venetian-Renaissance-Baroque style by a Hollywood set designer.

Lucius Beebe (r) and his partner, Charles Clegg, in the dining salon

Lucius Beebe (r) and his partner, Charles Clegg, in the dining salon of their private railroad car, The Virginia City.

The editorial policy of The Territorial Enterprise under Beebe’s stewardship was, as one reader characterized it, “pro-prostitution, pro-alcohol, pro-private-railroad cars-for-the-few and fearlessly anti-poor folks, anti-progress, anti-religion, anti-union, anti-diet, anti-vivisection and anti-prepared breakfast food.” When Virginia City went up in arms about a brothel located near a school, he resisted efforts to move the brothel, sloganeering, “Don’t move the girls; move the school.”

On having been a New York society columnist, he wrote: “I considered my function that of a connoisseur of the preposterous… I did have a fabulous time. I did drink more champagne and get to more dinner parties and general jollification than I would have in almost any other profession.”

Lucius Beebe turned his back on it to ride the rails of his imagination into the West and a bygone era. When a friend complained that if Thomas E. Dewey was elected President it would set the country back 50 years, Beebe replied “And what was wrong with 1898?” Indeed, it was the Gilded Age, the height of railway travel and steam locomotive splendor.

Beebe had come home.

________

Tomorrow: An Illustrated Checklist of the Railroading and Western Americana Books of Lucius Beebe, Bon Vivant.

_____________

Thanks to Barbara Humphreys of Pawcatuck, CT for the suggestion.

Read A Paper Is Born: A History of the Territorial Enterprise by Lucius Beebe here.

The transcript of an oral history by famed rare book dealer and small press publisher, Warren R. Howell, can be read here.

Photo gallery courtesy of New York Social Diary, which has an excellent article about Beebe on its website.

The Lucius Beebe Memorial Library is located in Wakefield, MA.