Photomechanical print: color; 41 x 51 cm. Artist: “Christian.”

A sultry, heavily-made-up woman squints provocatively, while smoking a cigarette. WWII posters usually addressed men, and fingered promiscuous women as the source of contagion.

They are an unholy alliance of science, art, medicine, politics, history, advertising, and propaganda. Dramatic images use visual shorthand to convey danger, disease, and death. Shadows, crowds, skeletons, vermin, blob-like micro-organisms, and sinister sick-o’s threaten innocent men, women, and children. But these aren’t posters for grindhouse horror flicks from the fabulous 50’s. They’re government issue placards pleading for public health.

Chinese Anti-Tuberculosis Society, 1935.

Chinese Anti-Tuberculosis Society, 1935.Translation: “Mistakes are difficult to avoid. Mistakes can be corrected once people realize their errors; and people can be forgiven, if the mistake is not committed again. In spite of government efforts, the average person still does not think spitting is wrong. Any time, any place. Spit once, spit again. Not only does this lack public morality, but, if the phlegm contains the TB bacillus, this can spread thousands upon thousands of bacilli. Spit, on the ground, or on common tools, is inhaled into the lungs. People next to you don’t know or feel it, but can catch the disease. TB is rampant in our country because of the error of spitting anywhere. This is unforgivable! If you have the habit, please stop doing it. Spit into a handkerchief and boil it, or spit into paper and burn it. This not only ensures virtue but is a gift to mankind.”

The Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences (CPNAS) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM) of the National Institutes of Health have teamed up to create an exhibit of 22 posters from around the globe, the creme de contagion culled from a collection of hundreds of compelling commercials created to curtail communicable killers. An Iconography of Contagion proves that every trick in Madison Avenue’s persuasive playbook was purloined by medical professionals to stem the tide of spitting, sneezing, screwing around, smoking, and other socially suspect steps certain to spread sickness.

Rotten er en Landeplage. (Rats are a plague on the land.)

Rotten er en Landeplage. (Rats are a plague on the land.)Statens Annonce & Reklamebureau, Denmark, 1946.

Color lithograph; 54 x 86 cm.

Artist: Aage Rasmussen (1913-1975).

A rat crawls over a map of Denmark. The caption reads “Anmeld straks Rottebesog paa kommunekontoret-og Bekæmp selv med alle midler.” (“Immediately tell the city authorities if you have rats in your house, and use all possible means to exterminate them”).

The first goal of the health poster is to attract the viewer’s attention. Through seduction, entertainment, annoyance, or fear, the images and words on the poster must capture the intended audience. Once heeded, it is hoped the message of the campaign will exert a powerful effect on behavior. Through a combination of argument and imagery, the content will persuade the populace to carry a handkerchief, see a doctor, get an x-ray, practice safer sex, drink only clean water, destroy disease-carrying vermin, get vaccinated, stop smoking, exercise, and practice good nutrition.

She may look clean, but…pick-ups, “good time” girls, prostitutes spread syphilis and gonorrhea.

She may look clean, but…pick-ups, “good time” girls, prostitutes spread syphilis and gonorrhea.U.S. Public Health Service,United States, 1940s.

Photomechanical print: color; 37 x 51 cm.

An appealing, seemingly innocent, young woman smiles. Three men, a sailor, a civilian and a soldier, look toward her.

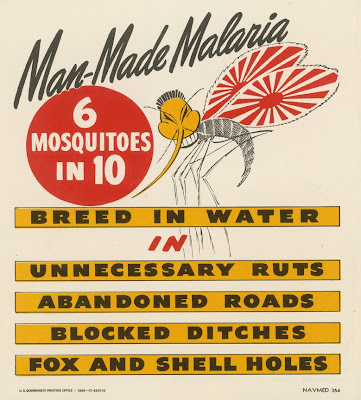

Man-Made Malaria. 6 mosquitoes in 10 breed in water in unnecessary ruts, abandoned roads, blocked ditches, fox and shell holes.

U.S. Navy, Bureau of Medicine & Surgery, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1945.

Photomechanical print: color; 21 x 23 cm.

War-time U.S. military health campaigns often conflated the Japanese enemy with disease-carrying flies and mosquitoes. Here, an anopheles mosquito is given the stereotypical features of the Japanese enemy and has the rising sun of the Japanese imperial flag on his wings.

Scientific advances in the 1950s, antibiotics, the polio vaccine, made public health posters seem passe. The general populace believed drugs and technology would quickly eradicate all the plagues of humankind. Then, in the 1980s, a new incurable killer came knocking. “AIDS blew a giant hole in that belief,” says Sappol. HIV/AIDS posters took advantage of the more liberal social climate, and selected salty language and saucy images to sell safe sex. They took a stab at soothing irrational fears, too, assuring a panicked public that casual contact couldn’t cause contamination. “Don’t worry about what you’ll pick up at work,” says the text of a poster showing a hand touching a coffee cup, and reaching for a towel and a wrench.

Don’t worry about what you’ll pick up at work.

Health Education Authority, Great Britain, 1980s.

Photomechanical print: color; 60 x 42 cm.A series of ominous photos of darkly-lit human hands touching or grasping for objects commonly used in the workplace. The caption reassures the public that hands and the objects they touch are not carriers of the AIDS contagion.

Discover safer sex.

Terrence Higgins Trust, London, mid-1980s.

Photomechanical print: color; 42 x 60 cm.

This poster, from the Love Sexy, Love Safe campaign, shows an intimate scene of a couple in bed. A tattooed man places his head between the legs of a sexually indeterminate partner. The precise nature of the activity is playfully obscured. Against the stigmatization of gay sex and AIDS sufferers as a source of contagion, and a larger atmosphere of panic, the poster presents sexual activity in a positive light and urges the use of reasonable measures to make sex safe.

Infectious diseases form a chain that links not just all of humanity, but all living things. They do not discriminate, they affect every individual and every population. They have shattered societies and eliminated entire economies. They have changed history by determining the outcome of warfare, destroying the demography of nations, and creating social unrest. They still make headlines every day, and remain mysterious despite scientific breakthroughs. We remain vulnerable to new illnesses in spite of all of our education and technology. Malaria still kills more than 1 million people a year; AIDS has taken more than 25 million lives. Little has changed since 1934, when Hans Zinsser wrote in his classic study, Rats, Lice and History: “Infectious disease is one of the great tragedies of living things – the struggle for existence between different forms of life.”

Tuberkulose undersogelse –en borgerpligt (Tuberculosis examination – a citizen’s duty.)

Copenhagen, Denmark, 1947.

Color lithograph; 62 x 85 cm.

Designer/artist: : Henry Thelander (fl. 1902-1986).

Lithographers: Andreasen & Lachmann.

A shadow couple happily walks arm in arm. In the background, the abstract form of a modernist building, looking like an arrow and suggesting a statistical increase, is labeled Folke-tuberkulose undersogelse.

La course a la mort. (The race with death.)

Ligue Nationale Française contre le Peril Venerien, France, ca. 1926.

Color lithograph; reproduction of a pastel drawing; 69 x 88 cm.

Artist: Charles Emmanuel Jodelet (1883-1969).

Death watches a thoroughbred race of deadly diseases. The statistics below compare the annual mortality rates of tuberculosis, syphilis

and cancer.

“An Iconography of Contagion,” began life as a short term exhibition in Washington, D.C. Now in a trend that appears to be infectious, the National Library of Medicine has made the exhibit a permanent online feature of its website. The posters served a deadly serious purpose, but have an artistic legacy, as well. As curator Michael Sappol puts it: “they’re also about the pleasure of the image. There have been some very sexy, colorful, playful posters about some very serious diseases.”