To be fair, Amelia Earhart was a pioneer in aviation prior to meeting her personal P.T. Barnum, but she was completely unknown outside of flying circles. In 1922, she set an unofficial aviation record as the first female pilot to fly above 14,000 feet, and in 1923 she became the first woman, and seventeenth pilot, to receive a National Aeronautic Association pilot’s license. But by 1924 she had sold her plane and given up flying, primarily due to family financial struggles.

After Charles Lindbergh‘s historic 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic, a wealthy dilettante, Amy Phipps Guest, became enthralled with the idea of being the first female to cross the ocean by air. She purchased a tri-motor Fokker aircraft and planned to hire a crew to take her on the flight. (Guest would travel as a passenger rather than a pilot.) Once the dangers and hardships of early air travel became all too apparent, Amy Phipps Guest wisely grounded herself, and instead offered to finance the solo voyage of “another girl with the right image.” Enter book publisher and publicist George Palmer Putnam, grandson of famed publishing company founder G.P. Putnam, who was tasked with finding a woman with “the right stuff,” and polishing, packaging and promoting a promising pilot into a planetary-circumnavigating star.

Amelia Earhart was in her second year as a social worker at Boston’s Denison House when she received a call from Putnam’s partner in the piloting project, Hilton H. Railey. Would she be interested in becoming the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air? An interview with Railey and Putnam followed, and Earhart passed the audition to become a passenger aboard the “Friendship,” a FokkerF.VII.b/3m, piloted by Wilmer Stultz and co-piloted Louis “Slim” Gordon. The three departed from Newfoundland on June 17, 1928, and landed in Wales exactly 20 hours and 40 minutes later. When interviewed after landing, Amelia said, “Stultz did all the flying…had to. I was just baggage, like a sack of potatoes. Maybe someday I’ll try it alone.”

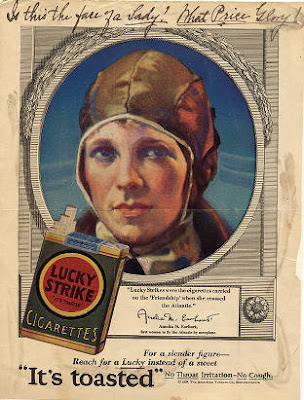

Thanks to Putnam’s P.R. machine, she soon gained international acclaim for being the first woman to make the transatlantic crossing by air. Pilots Stultz and Gordon were ignored by the press, and even President Coolidge cabled his congratulations to Amelia, personally. Upon her return to America, the woman who was a passenger-not a pilot-received a ticker-tape parade through the streets of New York City. Her book documenting the flight, 20 Hrs. 40 Mins., complete with an editing polish from Putnam, was published by (surprise!) G.P. Putnam’s Sons, in 1928.

George Putnam and company made sure Amelia’s name stayed in the headlines. His partner in publicity, H.H. Railey, noted Amelia’s many physical similarities to Lindbergh: both were tall and slender, with high cheekbones and an easy, “aw shucks” kind of grace that telegraphed down-home humility. Railey made sure his nickname for Amelia, “Lady Lindy,” became a staple of newsmen on both sides of the Atlantic. Amelia accepted a job as “Aviation Editor” of Cosmopolitan Magazine, ensuring plenty of ink for the pioneering passenger. Putnam arranged non-stop lecture tours for his media darling to promote her book. His accompaniment of Earhart on the lecture circuit led to a less glowing form of publicity: gossip. Putnam was a married man.

Not all of the gigs Putnam arranged for Amelia were unrelated to aviation. In 1929, Earhart was appointed Assistant to the General Traffic Manager at Transcontinental Air Transport (TAT), with a special responsibility of attracting women passengers. Earhart invested time and money in setting up TAT’s regional shuttle service between New York City and Washington, D.C. The move paid off when the early commercial airline continued to expand, and eventually became know as Trans World Airlines. Only once did Amelia refuse to navigate according to Putnam’s flight plan: he wanted to put her likeness on a small medal marketed for children. Amelia nixed the plan saying: “Forget it, George. I won’t be a part of cheating youngsters. Adults are supposed to know better, but not kids.”

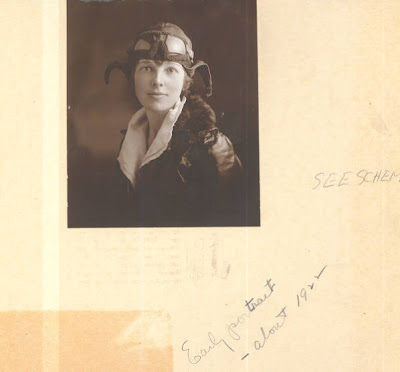

A Publicity Shot, circa 1932.

A Publicity Shot, circa 1932.Palmer instructed Earhart to “keep her mouth shut” to hide a gap-toothed smile.

Going Hollywood, 1932. Amelia Shows Actress Claudette Colbert The Bracelet She Wore While Crossing The Atlantic.

Going Hollywood, 1932. Amelia Shows Actress Claudette Colbert The Bracelet She Wore While Crossing The Atlantic.Just as with the 1928 flight Amelia took as a passenger, by 1932 Putnam was well aware that a woman would soon pilot a plane across the Atlantic, emulating Lindbergh. Putnam wanted Amelia to be that woman, as much as Earhart yearned for the honor herself. On May 20, 1932, exactly 5 years after the Lindbergh flight, Amelia’s modified Lockheed Vega began the journey. Earhart set off from Newfoundland and after a flight lasting 14 hours, 56 minutes, and plagued by mechanical problems and icy weather conditions she landed in Northern Ireland. Upon completing this flight, Amelia became the first woman (and second person) to fly solo across the Atlantic. She also became the first person to cross the Atlantic twice by air nonstop, setting a record for the fastest Atlantic crossing and the longest distance ever flown by a woman.

Purdue University President Edward C. Elliott invited Amelia Earhart to joined the university’s faculty as a career counselor for women interested in non-traditional occupations, and as an adviser to the Department of Aeronautics. The university funded the purchase of what she called her “flying laboratory,” a Lockheed Electra airplane that was to be used for her greatest flying adventure to date: a round-the world-flight at the equator. Her initial attempt at circumnavigating the globe, flying westward from Oakland to Hawaii, ended with a crash on the island of Oahu. The badly damaged plane had to be sent to California for repairs. On June 1, Amelia began her second global flight attempt, taking off from Miami with navigator Fred Noonan, traveling from west to east. After completing 22,000 miles of the flight, Earhart and Noonan left New Guinea en route to tiny Howland Island. They hit bad weather, and lost radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca on July 2, 1937. Despite a massive search authorized by the U.S. government, no trace of Earhart, Noonan, or their plane was ever found. George Putnam financed his own search for his missing wife until October 1937. In 1939, Amelia Earhart was declared legally dead in Los Angeles.

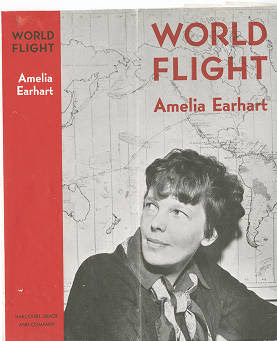

Proof of Book Cover June 30, 1937. The Title Would Be Changed From World Flight To Last Flight When Earhart Vanished.

Proof of Book Cover June 30, 1937. The Title Would Be Changed From World Flight To Last Flight When Earhart Vanished.

Putnam published a book of journal entries from the fatal flight which had been planned when Amelia began her initial attempt at a flight around the equator. The book was to have been titled World Flight but was printed under the title Last Flight. Most historians agree that Putnam wrote much of the book himself, a tribute to the woman whose place in history he helped to secure.

After his wife’s disappearance, Putnam donated thousands of letters, maps, documents, flight plans, and even Amelia’s flight suits, helmets, and personal items from her flight kits, such as makeup and smelling salts, to the Purdue University Library, where these items comprise the George Palmer Putnam Collection of Amelia Earhart Papers. The exhibit, which opened on March 1, 2010, Amelia Earhart: The Aviator, the Advocate, and the Icon, draws upon the world’s largest collection of Earhart artifacts, housed at the Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center in West Lafayette, IN. It is the first time such as exhibit has been mounted since 2003, and opens as a celebration of both Amelia Earhart and Women’s History Month. Most of the collection has also been digitized, so it is available online for those unable to grab a flight to the Hoosier State. Almost 75 years since his wife disappeared without a trace, public relations genius George Palmer Putnam is still keeping Amelia Earhart in the public eye.