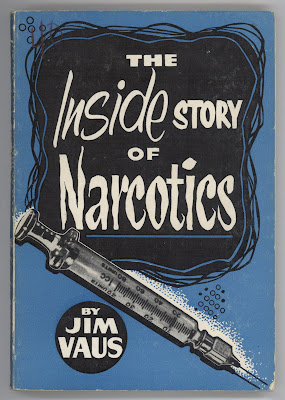

In 1953, a paperback book, The Inside Story of Narcotics, was issued by religious publishing house, Zondervan. Released at the height of hysteria about a national epidemic of teen-aged junkies that did not exist, it was written by one Jim Vaus.

“Every trade has a technical language. Even Christians have a language of their own. They speak of being ‘saved,’ of a ‘Christian worker,’ or of ‘putting out fleece.’ The person not used to their jargon doesn’t understand what the Christians are talking about. Addicts, too, have a language of their own, language which must be understood if this book is to be understood. Some of the words most used are: bad go – too small an amount for the money paid; bang – an injection of heroin’ blast party – a get together to smoke marijuana.”

Vaus, it turns out, was one of the most interesting characters to have ever put pen to pulp. He was, until recently, a lost footnote in Los Angeles history, a man who stood at the shadowy nexus of Los Angeles politics, the underworld, and the LAPD. He then took a sharp turn and wound up connecting evangelist Billy Graham to that dark triad.

“Wiretapper Jimmy Vaus couldn’t decide whether he wanted to be a cop or a crook – so he tried to be both. In doing so, he set off on a path that led directly to Mickey Cohen,” the L.A.-born gangster who tried to make it in Chicago and Cleveland before returning to the City of Angels to eventually become Southern California’s foremost fallen one.

“Wiretapper Jimmy Vaus couldn’t decide whether he wanted to be a cop or a crook – so he tried to be both. In doing so, he set off on a path that led directly to Mickey Cohen,” the L.A.-born gangster who tried to make it in Chicago and Cleveland before returning to the City of Angels to eventually become Southern California’s foremost fallen one.

A sound engineer and electronics specialist during Army service, in 1946 Vaus was managing an apartment building in Hollywood while pursuing his passion for electronic wizardry. A working girl living in the building was upsetting the other tenants. Vaus called the vice squad. The vice squad officer who responded had no way to catch her in the act; he could hear voices behind the girl’s door but could not make out what was being said. Incredulous that the LAPD did not have electronic surveillance equipment to listen in on her conversations, Vaus volunteered his services. Vaus provided the LAPD with its first wiretapping equipment and operated it. The prostitute was busted. The wiretap was illegal but no matter – this was the LAPD at its darkest noir.

Vaus’s success with the case prompted the LAPD to avail themselves of his ongoing services in their quest to prevent L.A. from becoming an “open” city for organized crime; in 1937, Ben “Bugsy” Siegel, the matinee-idol handsome mobster, had come to town at the behest of his associates in New York and Chicago to organize illegal activity. He brought in Mickey Cohen, a former street thug and featherweight boxer with hair-trigger temper and spastic trigger-finger, a wildly impulsive, near-illiterate punk with a rep for possessing the biggest pair of cajones for a little runt that ever wielded a .38, a shotgun, or whatever necessary to conduct business. He was sorcerer’s apprentice to Siegel, who cleaned, polished (as much as Cohen could be), and wised him up. By the time Siegel was murdered in 1947, Mickey had risen to become L.A.’s top mobster.

Vaus’s success with the case prompted the LAPD to avail themselves of his ongoing services in their quest to prevent L.A. from becoming an “open” city for organized crime; in 1937, Ben “Bugsy” Siegel, the matinee-idol handsome mobster, had come to town at the behest of his associates in New York and Chicago to organize illegal activity. He brought in Mickey Cohen, a former street thug and featherweight boxer with hair-trigger temper and spastic trigger-finger, a wildly impulsive, near-illiterate punk with a rep for possessing the biggest pair of cajones for a little runt that ever wielded a .38, a shotgun, or whatever necessary to conduct business. He was sorcerer’s apprentice to Siegel, who cleaned, polished (as much as Cohen could be), and wised him up. By the time Siegel was murdered in 1947, Mickey had risen to become L.A.’s top mobster.

This upset the LAPD no end. Soon, Vaus was tapping – illegally, ‘natch – Cohen’s phones and bugging his house.

Not long afterward, Vaus was involuntarily summoned to meet the Jewish Napoleon in sharkskin, who had learned of the taps and of the whiz behind them. Jim assumed the meeting would be his last on earth. To the contrary, Cohen asked him to tap and bug on his behalf.

“Confronted with such opulence [Cohen’s home], Vaus’s moral faculties, which were clearly weak to begin with, failed him entirely. ‘It would have been very hard to persuade a man that it was wrong to have the money sufficient to buy these creature comforts,’ Vaus concluded.”

The beginning of the Mickey/Vaus relationship (gangsters elsewhere in the U.S. considered Cohen’s operation “the Mickey Mouse Mafia”) was celebrated by Cohen backing Jim in an electronics shop, conveniently located in the same building on Sunset Boulevard as Michael’s Haberdashery, Cohen’s ersatz-class men’s shop. Cohen’s given name was Meyer. He’d come a long way since Boyle Heights, he fantasized.

Cohen employed Vaus to collect evidence of police corruption, specifically blackmail attempts against him by LAPD officers. There was a lot of evidence. He also had Vaus de-bug his home. This presented a problem.

Vaus was now working both sides of the street. But “even the covetous wiretapper understood that working for both the LAPD and the city’s top organized crime boss would be a dicey proposition.”

In Time magazine’s review of Wiretapper (1955) – “The true-life drama of the man who kept the Gangsters, the Gamblers and the Bookies always one step ahead of the law – until the moment when he tapped in on a direct line to God” – a movie adapted from Vaus’s autobiography, Why I Quit Syndicated Crime (Wheaton, Illinois: Van Kampen Press, 1954), it is noted that “the highlight of Jim’s criminal career was a slick trick for improving his judgment of race horses. He would cut into the direct Teletype wire between a bookie and the race track, take the race results on his own Teletype, and signal a confederate to place last-minute bets with the unsuspecting bookie before feeding the delayed tape back into the bookie’s wire again. He was about to leave for St. Louis to make a new installation of this type when he stepped into a Billy Graham rally.”

Vaus, whose father, James Vaus, was a Bible-thumping preacher, was ripe for conversion; the needle of his moral compass was spinning out of control and the omens for a long life ending by natural causes were not auspicious.

“The year 1949 had been a disastrous one for Jimmy Vaus. [The scandalous trial of a LAPD officer caught on one of Vaus’s wiretaps] and the revelations that followed had exposed him as a double agent and placed him in considerable peril.”

Billy Graham came to town in October of 1949 to begin a series of old-fashioned tent-meetings. Graham was a nobody until William Randolph Hearst took a shine to the charismatic religious figure and made sure his Los Angeles newspapers, the Examiner and Herald-Express, provided extensive and effusive coverage of the minister and his “Crusade for Christ.” This campaign by Graham would be his first. It made him a star, and launched his career as America’s Minister.

Billy Graham came to town in October of 1949 to begin a series of old-fashioned tent-meetings. Graham was a nobody until William Randolph Hearst took a shine to the charismatic religious figure and made sure his Los Angeles newspapers, the Examiner and Herald-Express, provided extensive and effusive coverage of the minister and his “Crusade for Christ.” This campaign by Graham would be his first. It made him a star, and launched his career as America’s Minister.

Vaus attended one of Graham’s meetings. Graham made a call for sinners, his famous “This is your moment of decision!”

“Suddenly, Vaus found himself gliding up the isle toward the platform at the front of the ten where Graham was standing. Then he was down on his knees. He left in a daze. As he was exiting the tent, a photographer’s lightbulb flashed. The next day, newspaper readers awakened to the headline WIRE-TAPPER VAUS HITS SAWDUST TRAIL.

“Jimmy Vaus had been born again.”

Through Vaus, Graham met Mickey Cohen, who the evangelist had set his sights on as a flashy potential convert; Cohen was going through one of his periodic and disingenuous “I’m goin’ straight” phases – a recent incarceration was so frightful that he never wanted to see the inside of a prison again. He played Graham as earnestly as Graham worked him. In the end, Cohen, despite his “sincere” desire, used Graham for cover, gave Graham the air, and left his salvation to the dice tables. But not before both had reaped the P.R. benefits.

Vaus, in the interim, wrote The Inside Story of Narcotics. Though he had virtually no experience with the drug trade in Los Angeles or anywhere else, his contacts in the LAPD’s vice squad provided him with all he needed to know. As Billy Graham’s star convert, the book was an exercise in redemption and sold well, going through at least four printings that I am aware of.

“These two men — one morally unflinching, the other unflinchingly immoral — would soon come head to head in a struggle to control the city — a struggle that echoes unforgettably through the fiction of Raymond Chandler and movies like The Big Sleep, Chinatown, and L.A. Confidential. For more than three decades, from Prohibition through the Watts riots, their struggle convulsed the city, intersecting in the process with the agendas and ambitions of J. Edgar Hoover and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Mike Wallace and Billy Graham, Lana Turner and Malcolm X and inspiring writers from Raymond Chandler to James Ellroy. Its outcome shaped American policing — for better and for worse — and helped to create the Los Angeles we know today” (From Buntin’s website).

“Packed with Hollywood personalities, Beltway types and felons, Buntin’s riveting tale of two ambitious souls on hell-bent opposing missions in the land of sun and make-believe is an entertaining and surprising diversion” (Publishers Weekly).

“LA Noir is a fascinating look at the likes of Mickey Cohen and Bill Parker, the two kingpins of Los Angeles crime and police lore. John Buntin’s work here is detailed and intuitive. Most of all, it’s flat out entertaining” (Michael Connelly).

I briefly discuss The Inside Story of Narcotics in my book, Dope Menace. Consider this post an extended end note to that volume.