Yesterday, PhiloBiblos wrote Selling Off Rare Books To Pay the Bills in protest against the decision by Rev. Stephen Privett, president of the Jesuit’s University of San Francisco, to sell items from the rare books and art collection of USF’s Gleeson Library.

This action has many dissidents.

I have many friends who are university librarians. The work that rare book/special collections director-curator-librarians do is extremely important and the ability of some of the best to identify a heretofore unexamined subject and acquire material related to it is one of the great illuminating services they offer to students, scholars and the public.

Philobliblos, who I do not know but admire for his book blog, writes:

“As I’ve said many times before, deaccessioning – legitimate deaccessioning – is a necessary part of an institution’s business, but doing so in this form and fashion is completely beyond the pale. Not only is selling off prize items from the collections just cutting off your nose to spite your face, it’s also an incredibly short-sighted way to deal with financial difficulties.”

In fairness to USF’s president, what is “legitimate deaccenssioning” if not to raise money? What other reason would an institution have to sell books from its collection, aside from getting rid of duplicates?

Has anyone considered that USF, a private institution with endowments invested in the equities markets along with virtually every other institution, may likely have experienced a precipitous decline in its investments that absolutely required some very painful decisions to be made? For all we know, USF may have invested some of its money with Bernard Madoff.

In an ideal world, the Library wouldn’t have to sell anything from within its holdings. At this time the economy is far from ideal and the need to raise cash, and fast – whether as an individual or institution – is a prudent survival strategy in a time of sharp financial downturn.

PhiloBiblos further reports, “History professor Martin Claussen is leading the charge against sales from the university’s collections, telling the student paper ‘Selling parts of the library collection in order to pay current costs is like burning the furniture to keep warm.’ He disagrees with Privett’s statements that any proceeds from sales would go to the rare book room: ‘Selling items in the Rare Book Room to pay for renovations that would keep them safe? That logic sounds odd.’”

It sounds odd to Classen because he’s conflating selling some books from the Rare Book Room to selling every book. There will be plenty of rare books left for the renovations to protect and keep safe.

As far as his analogy – “selling parts of the library collection in order to pay current costs is like burning the furniture to keep warm” – goes, it doesn’t hold. Equating the sale of an object to the destruction of an object is drama, not reality. But even if the analogy were strong, burning a few chairs (not the house) to keep from perishing during a cold night is not something that anyone freezing would give a second thought to; Granny’s 100 year rocker has got to go – after all, the chair isn’t actually Granny, it’s her chair. And who said anything about burning every stick of furniture? The issue is not akin to the burning of the ancient library at Alexandria.

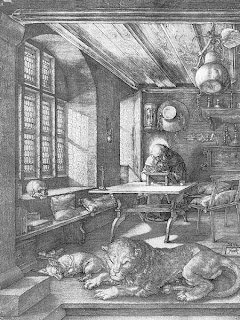

The for-sale items that have drawn the greatest ire of the dissenters are woodcuts, engravings or etchings, which is to say, they are not one-off, unique pieces. But there is anger that the collections’ integrity will be compromised if pieces from it are sold. There is some truth to that but to require that institutional collections be sold in toto to preserve their integrity would put an overwhelming burden upon university librarian-curators and their ability to be flexible. The biggest compromise to the integrity of the collection seems to be the selling of a print (not the original engraved plate) of Dürer’s St. Jerome in His Study. PhiloBiblios quotes a source of Terry Belanger, founding director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia and University Professor and Honorary Curator of Special Collections:

“In a down market, only the Rembrandt and a few of the Dürers sold [Specifically of the St. Jerome print]. St. Jerome is the patron saint of librarians whose feast day is September 30th. Traditionally, every September his engraving was exhibited in the Gleeson Library to bring blessings and protection to the Library itself, to the librarians who selflessly work there, and to all those who research and patronize it. Whose or what image will now bless and protect USF’s Gleeson Library? Perhaps, come next September, some one will hang black mourning cloth where once the image of St. Jerome was displayed.”

“In a down market, only the Rembrandt and a few of the Dürers sold [Specifically of the St. Jerome print]. St. Jerome is the patron saint of librarians whose feast day is September 30th. Traditionally, every September his engraving was exhibited in the Gleeson Library to bring blessings and protection to the Library itself, to the librarians who selflessly work there, and to all those who research and patronize it. Whose or what image will now bless and protect USF’s Gleeson Library? Perhaps, come next September, some one will hang black mourning cloth where once the image of St. Jerome was displayed.”

Or, perhaps, a picture of USF president Stephen Privett who had the courage to make a decision that was guaranteed to royally piss off purists but guaranteed that the integrity of the Library as a whole would survive.

Let’s be honest. The decision making process at any institution can be a long, drawn out, grueling and exhausting ordeal. The financial peril USF faced must have been acute. Had Privett taken the issue to committee for discussion, they’d likely still be discussing, arguing, protesting, revolting six months from now.

Is it unfortunate that the Library has had to sell a few items? Indeed. Is it a catastrophe? No.

A last word. The items from USF’s Gleeson Library were sold at auction. To the public. To be recirculated to private collectors. In other words, out of the confines of an institution and back out into the light of day to be dearly appreciated by a real, live, passionate person, not a cold abstract like “the public.”

The policy of the Gleeson Library’s rare book room:

“The Donohue Rare Book Room and the collections housed there are open to the University Community and other qualified users.” Meaning the books and artwork are not really, after all, available to the general public, which is as it should be; rare artifacts require careful conservatorship.

Whether antiquities belong to the public or anyone who can afford to own them is another subject for another time. I do know, however, that as much as university librarians love, appreciate, and value the books in their collections – tens of thousands – they do not have the time to lavish attention upon each one of them, in contrast to the private book lover with a relatively small collection who has the pride and exuberance of ownership.

I also know that eleven years ago, after putting it off for as long as I could, I sold the vast majority of my book collection. I desperately needed the money. For years I had put so much of myself into the books that to sell even one would have been like selling a kidney to pay the rent.

It wasn’t a kidney. I survived. In fact, as a consequence, I thrived afterward. It is almost as if, by fetishizing my collection, I had become a prisoner to it. To be possessed by one’s possessions is to close one’s self off. After a brief period of mourning, I felt a sense of elation, of liberation. Life went on; it even opened up and improved.

The Gleeson Library will survive. With the influx of cash, it may even get better. And if those who feel that without St. Jerome in His Study to bless and protect the library they are doomed, let me reassure them that, from what I know of Christian theology, St. Jerome with be there to bless and protect the library whether or not Dürer’s engraving is publicly displayed once a year. In fact, I suspect that God might be offended by all the rending of clothes:

“Thou shalt not worship graven images.”